Industrial control systems (ICS) and supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) networks increasingly rely on Windows-based platforms for efficient data collection, automation, and remote monitoring. Manufacturing plants, power grids, water treatment facilities, and other critical infrastructure sites often incorporate a mixture of legacy equipment and modern software tools. While this convergence boosts productivity and ease of management, it also introduces significant cybersecurity challenges. Attackers who manage to compromise a single Windows machine in an ICS environment can potentially disrupt physical processes with real-world consequences. Maintaining robust defenses in these specialized systems demands a strategic combination of network segmentation, stringent access controls, and ongoing collaboration between operations teams and traditional IT security personnel.

An initial hurdle is the blending of historically separate domains: operational technology (OT), which oversees physical processes, and information technology (IT), which handles data-centric operations. ICS networks typically prioritize reliability, ensuring processes like assembly lines or chemical mixing run continuously. By contrast, traditional IT places heavy emphasis on data confidentiality and integrity. As more ICS environments integrate Windows servers for data logging, remote support, or system administration, these differences in focus can create gaps. For example, patching a Windows machine in an ICS network might require downtime that OT staff find unacceptable, leading to postponed updates and expanded risk of unpatched vulnerabilities. Recognizing and reconciling these conflicting priorities is key to preventing ICS environments from becoming easy targets for ransomware, zero-day exploits, and advanced persistent threats (APTs).

Legacy systems further complicate security efforts. Many industrial sites still operate machinery designed decades ago, often running outdated Windows versions—like Windows XP or Windows 7—no longer supported by standard patches. Retrofitting new security measures onto these older platforms can be challenging, especially if specialized hardware or proprietary software depends on them. Some manufacturing lines cannot upgrade to a newer Windows release without extensive recertification or equipment overhaul, forcing administrators to rely on compensating controls like network isolation or custom firewalls. Thorough risk assessments help determine which systems pose the greatest potential impact if compromised, guiding decisions about how to allocate security resources. In some instances, organizations choose to sandbox older, vulnerable machines behind strict segmentation, letting them handle only the minimal tasks necessary to keep production going while shielded from main corporate networks.

Even modern Windows systems in ICS contexts are subject to specialized needs. Many industrial processes are time-sensitive; a few milliseconds of latency could damage equipment or spoil production runs. Excessive intrusion detection scanning, frequent patch reboots, or resource-heavy antivirus solutions might introduce delays that interfere with critical tasks. Finding a balance between thorough security monitoring and minimal disruption remains an ongoing process. Some organizations rely on “mirroring” or “tap” devices to passively inspect network traffic without slowing ICS operations. Others use finely tuned whitelisting solutions on Windows endpoints, permitting only a narrow set of approved executables to run, thereby cutting down on overhead and restricting possible malicious code from executing.

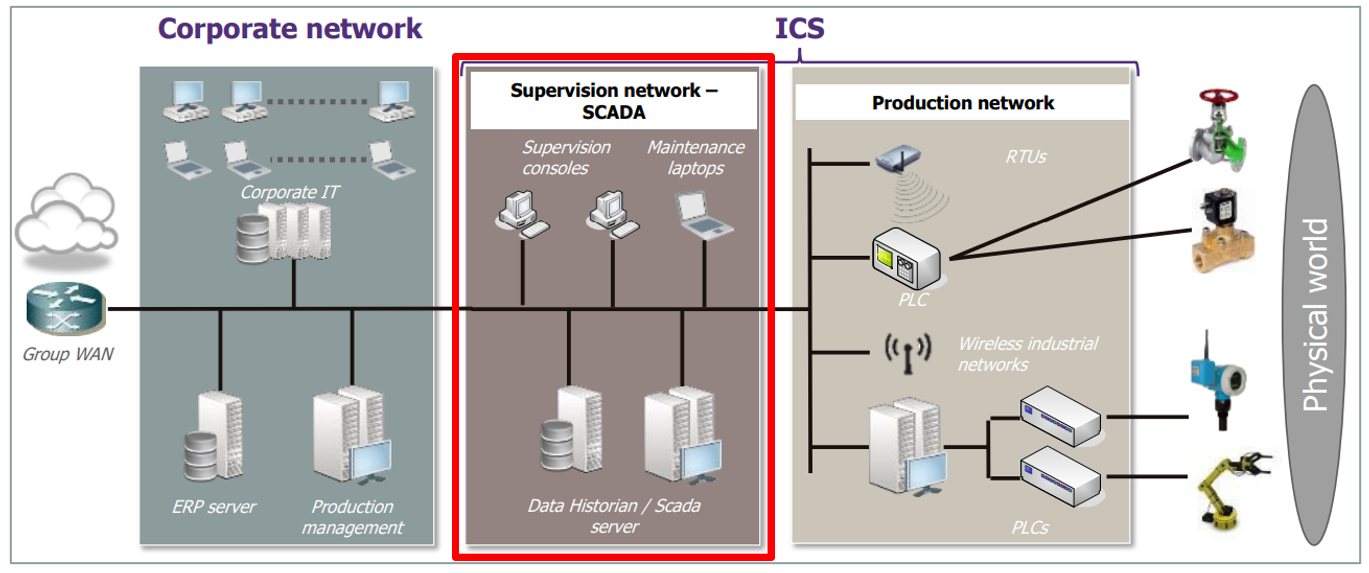

Network segmentation stands out as a central strategy. By establishing “zones” or layers, each with its own firewalls and access policies, security teams can limit how far a compromise can spread. An attacker who breaches a Windows-based engineering workstation in the corporate zone should not automatically gain access to controllers on the plant floor. The widely adopted Purdue Enterprise Reference Architecture offers a reference for layering networks, from enterprise systems in Level 4 or 5, down to the real-time control layers in Levels 1 and 0. Practical implementation involves configuring Windows devices in each layer to communicate only with specified hosts using defined protocols. Even if a Windows file server or historian sits in a DMZ between corporate IT and operations, carefully written firewall rules can confine traffic to legitimate communication paths. This approach helps to ensure that malicious software or unauthorized commands do not silently traverse the entire ICS environment.

Identity and access management can be more intricate in industrial settings than in typical office environments. Operators managing ICS devices may require shared logins for certain console access or specialized engineering tools. Traditional Active Directory authentication might not always apply if some devices run older Windows editions or proprietary software. Companies often adopt role-based access control (RBAC) to specify which tasks each operator can perform, mapping it to carefully managed Windows security groups. Multi-factor authentication (MFA) is challenging in some ICS scenarios where physical constraints or time-critical tasks prevent typical smartphone-based codes or tokens. Yet, whenever feasible, MFA drastically reduces the risk of credential theft leading to widespread sabotage. Where MFA isn’t practical, the organization can strengthen password policies, implement account lockouts after repeated login failures, and ensure frequent reviews of who holds administrative privileges.

Ongoing patch management is another cornerstone. Patching Windows servers, domain controllers, and operator workstations in ICS networks, however, can be a delicate balancing act. Scheduling downtime for essential updates requires careful coordination with production schedules. Some sites cluster multiple ICS servers for redundancy, allowing one server to be patched while the others run critical operations. Others rely on robust testing environments that replicate ICS workflows, verifying that patches won’t break drivers, SCADA applications, or specialized control logic. Although delays in patching are sometimes unavoidable, consistently postponed updates create prolonged windows of vulnerability. Security teams can mitigate this with compensating controls—like isolating an unpatched server behind more restrictive firewall rules—until the update can be safely applied.

Monitoring and anomaly detection benefit from a detailed baseline of normal ICS activity. Some industrial networks exhibit highly predictable traffic: Windows machines query sensors at fixed intervals, communicate with controllers at known frequencies, and generate data logs for historians. Deploying a security information and event management (SIEM) solution that integrates ICS-specific context can highlight suspicious anomalies, such as an unexpected spike in traffic from a Windows-based engineering workstation to a PLC (programmable logic controller) at 2:00 a.m. Similarly, strict ICS intrusion detection systems (IDS) examine protocol-specific patterns—like Modbus, DNP3, or OPC—for irregular commands or payloads. These tools can be invaluable, but they must be configured to avoid false positives that might overwhelm staff and lead to alert fatigue. Cross-training ICS and IT personnel fosters a mutual understanding of normal process data, speeding the identification of real threats.

Physical security interlocks with cybersecurity in ICS environments. For instance, an attacker doesn’t necessarily need to breach a firewall if they can enter a facility and plug into an open Ethernet port near critical controllers. Windows servers or desktops that manage ICS processes might be located in restricted areas, but sometimes these areas lack robust access controls or auditing. Tighter facility policies—keycards, biometrics, surveillance—provide an additional layer of defense, preventing unauthorized individuals from tampering with endpoints. Mobile devices or USB drives pose extra risks if introduced into ICS zones, as malicious code can hitch a ride on portable storage. Enforcing strict removable media policies and scanning everything before it’s connected can prevent accidental or deliberate infection of Windows-based control terminals.

Organizations are increasingly exploring cloud connectivity for data analytics and remote monitoring. While these capabilities enable advanced insights—such as predictive maintenance based on sensor data—they also open new attack vectors. A misconfigured cloud gateway could let unauthorized requests into the plant floor or expose Windows-based servers to the internet. Zero trust principles, which continually authenticate and authorize every request, can reduce risk. In practice, zero trust might involve micro-segmentation for each microservice or sensor feed and digital certificates for each Windows system. Combined with minimal open ports, end-to-end encryption, and close watch on inbound and outbound traffic, these configurations ensure that cloud integration doesn’t undermine ICS security.

By bridging the divide between IT best practices and the operational exigencies of ICS, organizations can effectively protect Windows-based control systems. This entails regular communication among security analysts, engineers, plant managers, and vendors. Some companies form cross-functional security operations centers (SOCs) focusing specifically on ICS, building teams equipped with the domain knowledge necessary to decipher process anomalies. Regular training helps all staff—operators, technicians, administrators—understand the ramifications of ignoring updates, disabling firewalls, or sharing passwords. While ICS security often involves trade-offs related to uptime and legacy systems, a well-coordinated approach can maintain productivity while safeguarding against modern cyber threats. The result is not just compliance with industry standards or regulatory requirements, but a stable, resilient infrastructure that underpins critical industrial operations without succumbing to digital sabotage.